A Reflection

By jacky feng

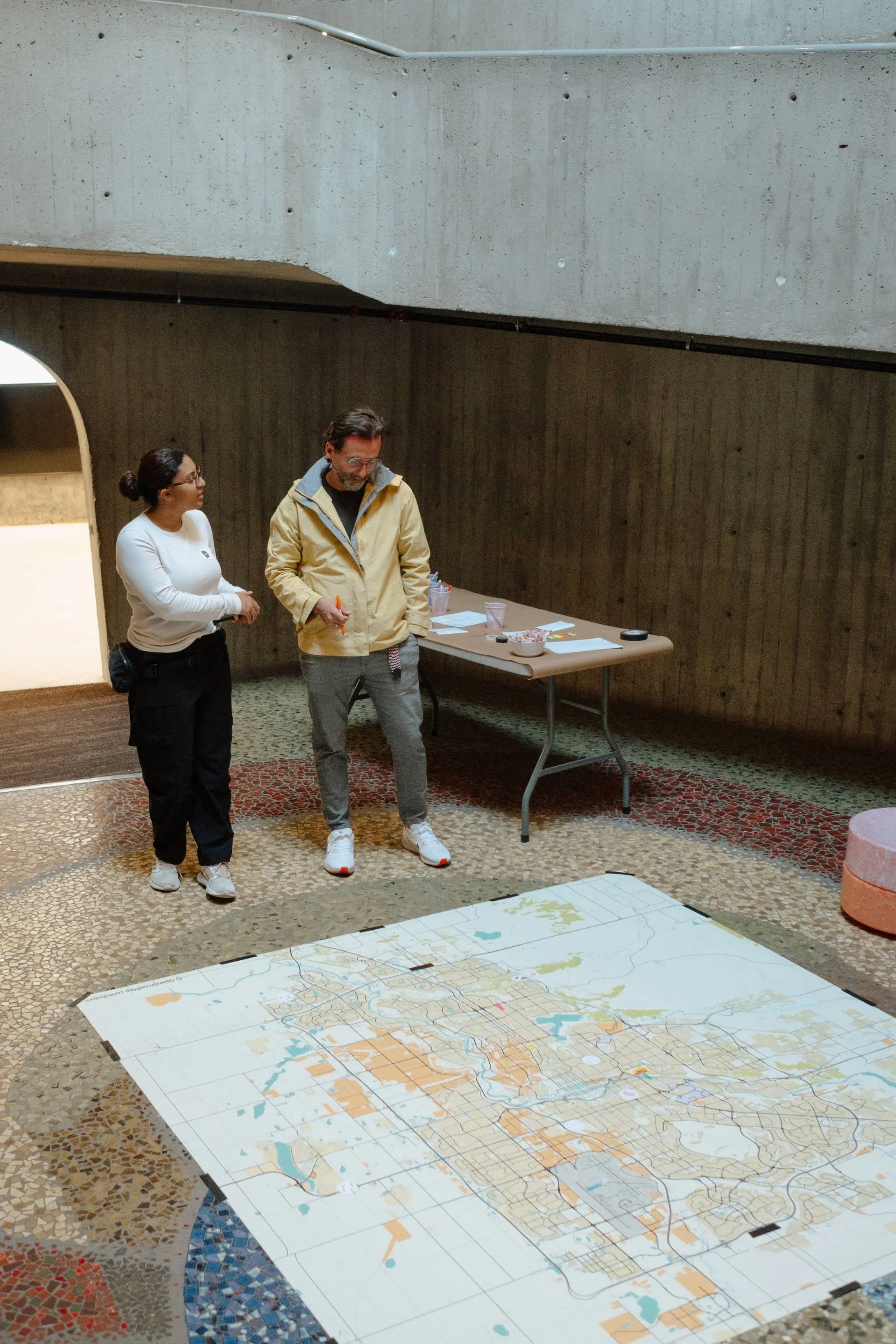

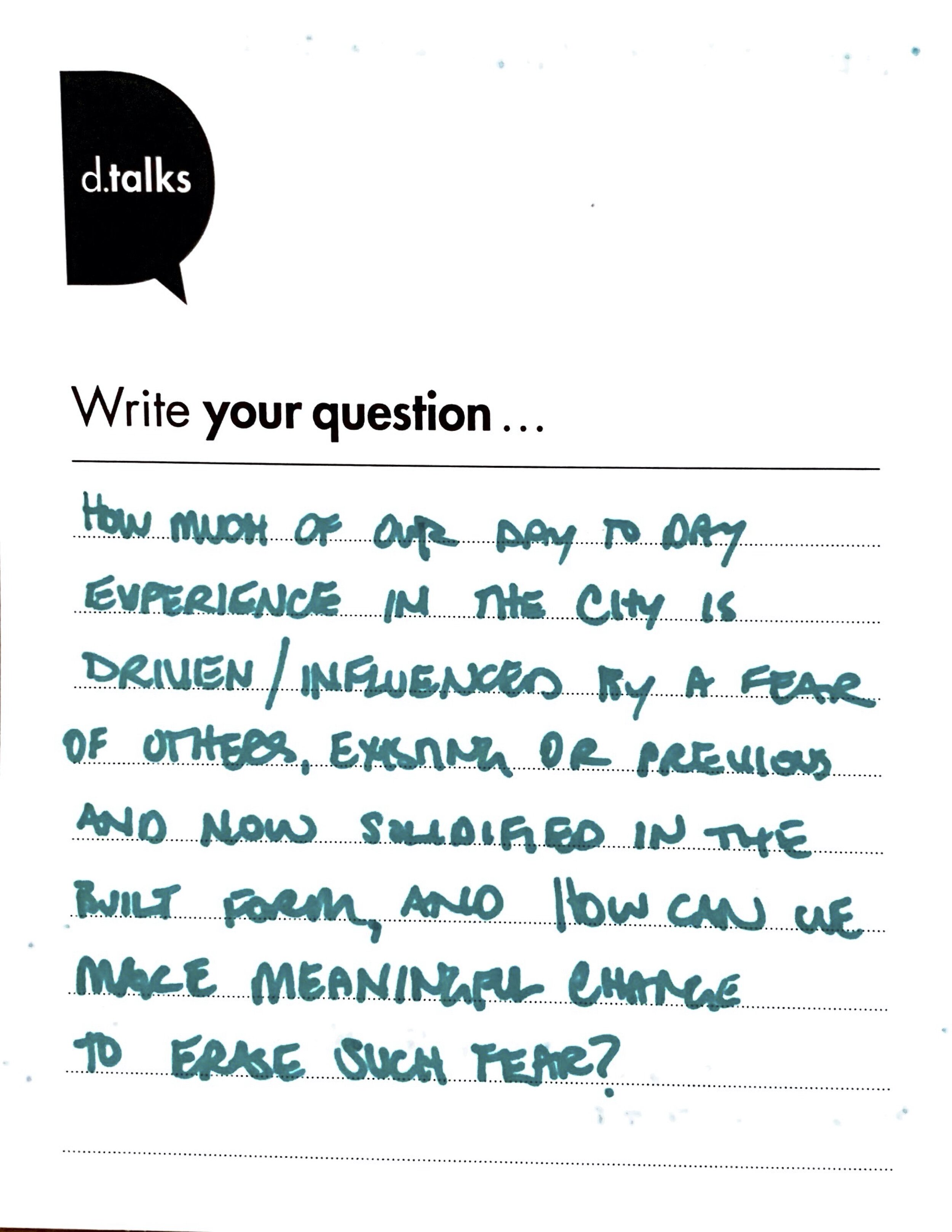

The “Let’s Talk About… Wanderlust” event at Contemporary Calgary on June 18, 2024, ignited a vibrant exploration into the intersection of art, community, and identity. Anchored by the theme of “placemaking,” the evening unfolded with reflective panels, immersive installations, and insightful discussions exploring how public art and design contribute to creating places rather than mere city spaces.

Guests stepped onto Clark Thenhaus’s Contemporary Confetti at the front plaza of Contemporary Calgary, setting the stage for stimulating discussions. Interactive pop-up activities highlighted the power of art, including a DIY tote decorating table where participants could create their own Contemporary Confetti with stencils and fabric markers.

Photo by Vikram Johal of Design Calgary

BEFORE: Photo by Vikram Johal of Design Calgary

AFTER: Photo by Vikram Johal of Design Calgary

Photo by Allison Seto

Photo by Allison Seto

Clark Thenhaus, the artist and architect of Endemic Architecture behind Contemporary Confetti, delved into the transformative power of art and space, advocating for engaging, interactive urban environments. His insights on “wallflower urbanism” highlighted the potential of art, like his urban confetti pop-up paint series, to activate and redefine public spaces. More importantly, he underscored how art fosters community engagement and dialogue, making everyone feel connected and part of a larger narrative.

Clark Thenhaus: photo by Allison Seto

Indigenous artist Jared Tailfeathers took the stage and emphasized the transformative power of art in reshaping community narratives. He highlighted the importance of having a sense of wanderlust, which allows us to go beyond the city’s surface, uncovering and sharing its hidden voices. Tailfeathers also emphasized the impact of art and storytelling in placemaking through his involvement in projects such as the Central Library’s permanent Indigenous art installation.

Jared Tailfeathers: photo by Allison Seto

The central portion of the event was a speaker panel moderated by Latosia Campbell-Walters. She facilitated a dynamic discussion on the role of public art in building community and creating wanderlust.

Panelists Caitlind R.C Brown and Wayne Garrett, a public art artist-duo, illuminated their artistic process, emphasizing community collaboration and the creation of meaningful, site-specific installations. They spoke about how Calgary is a city hungry for art and how art becomes a shortcut to creating meaningful places that generate memories.

Latosia Campbell-Walters: photo by Allison Seto

Caitlin RC Brown and Wayne Garrett: photo by Allison Seto

Former City Councillor Druh Farrell underscored the importance of beauty and belonging in urban design. Her advocacy for creating aesthetically pleasing, inclusive spaces was a powerful affirmation of the city’s commitment to enhancing civic identity. Her words made the audience feel valued and considered in the city’s design, fostering a sense of belonging and pride.

Lastly, Jessa Morrison from Brookfield highlighted the intersection of art, transit, and community experience. She articulated the role of art in enriching urban environments and fostering community cohesion, showcasing how thoughtful programming enhances tenant retention and community engagement.

Druh Farrell: photo by Allison Seto

Jessa Morrison: photo by Allison Seto

The “Let’s Talk About… Wanderlust” event was a testament to Calgary’s vibrant cultural landscape and its commitment to art as a catalyst for community connection. As we navigate the evolving urban fabric, art installations like Contemporary Confetti remind us of art’s transformative power in shaping our collective identity and fostering a sense of place.

Through art and dialogue, the notion of wanderlust continues to inspire us to reimagine our urban spaces, honoring diversity and amplifying voices that enrich our shared experience. Druh Farrell’s words resonate: “Let us create a sense of belonging in our city, a place that makes people want to stay and write songs about.”

Shannon Lanigan, Co-Founder and Managing Director of d.talks: photo by Allison Seto

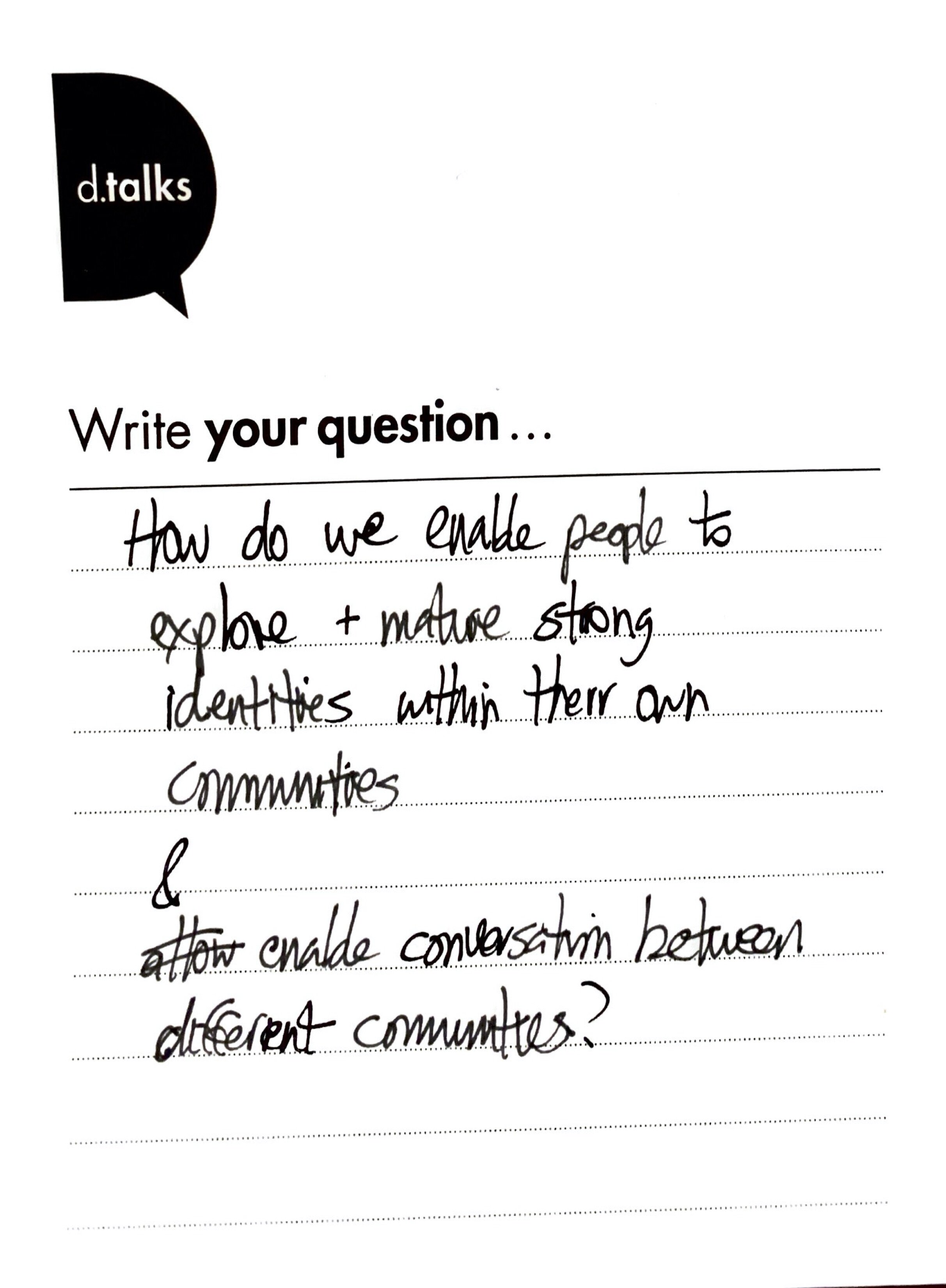

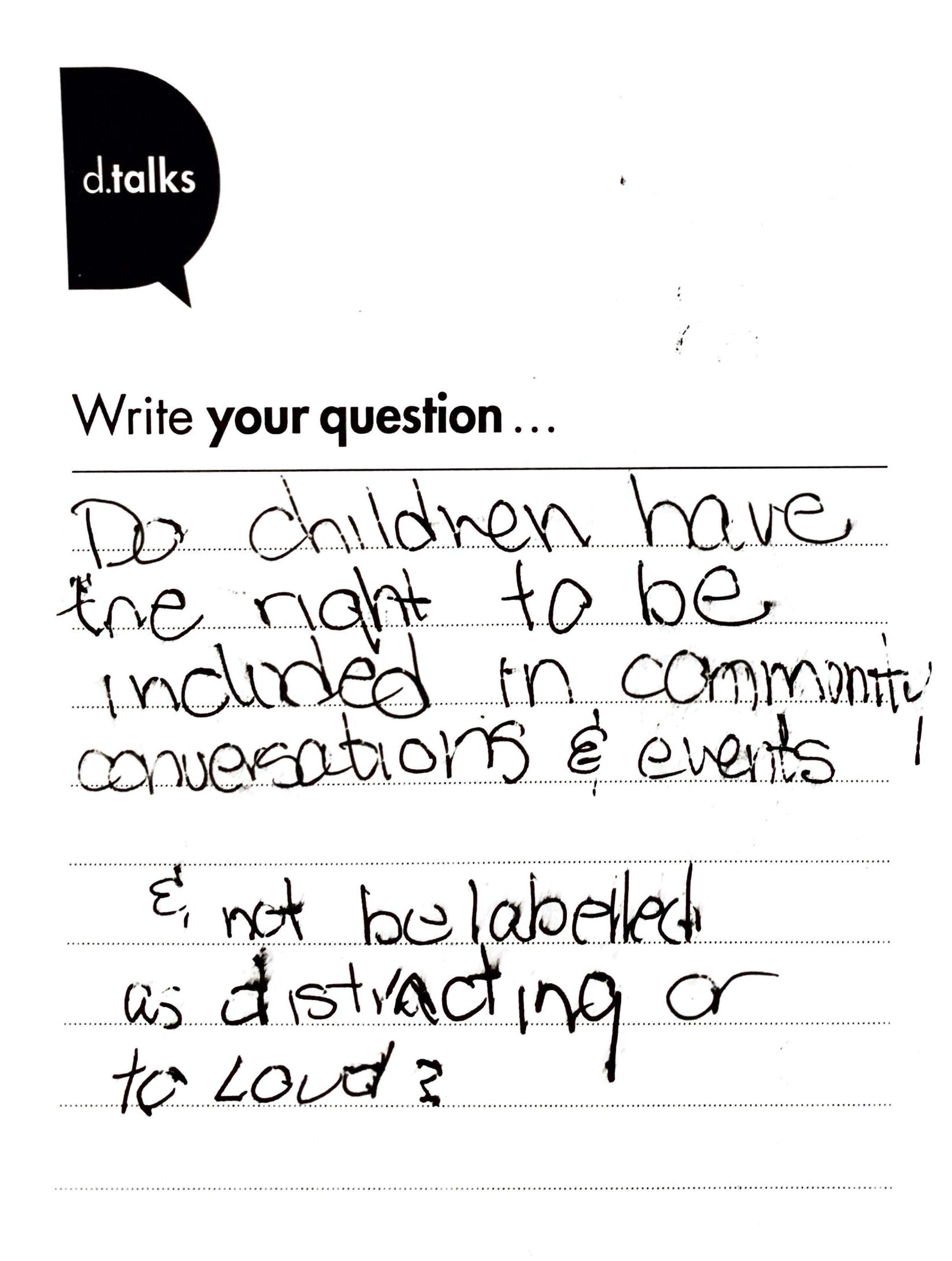

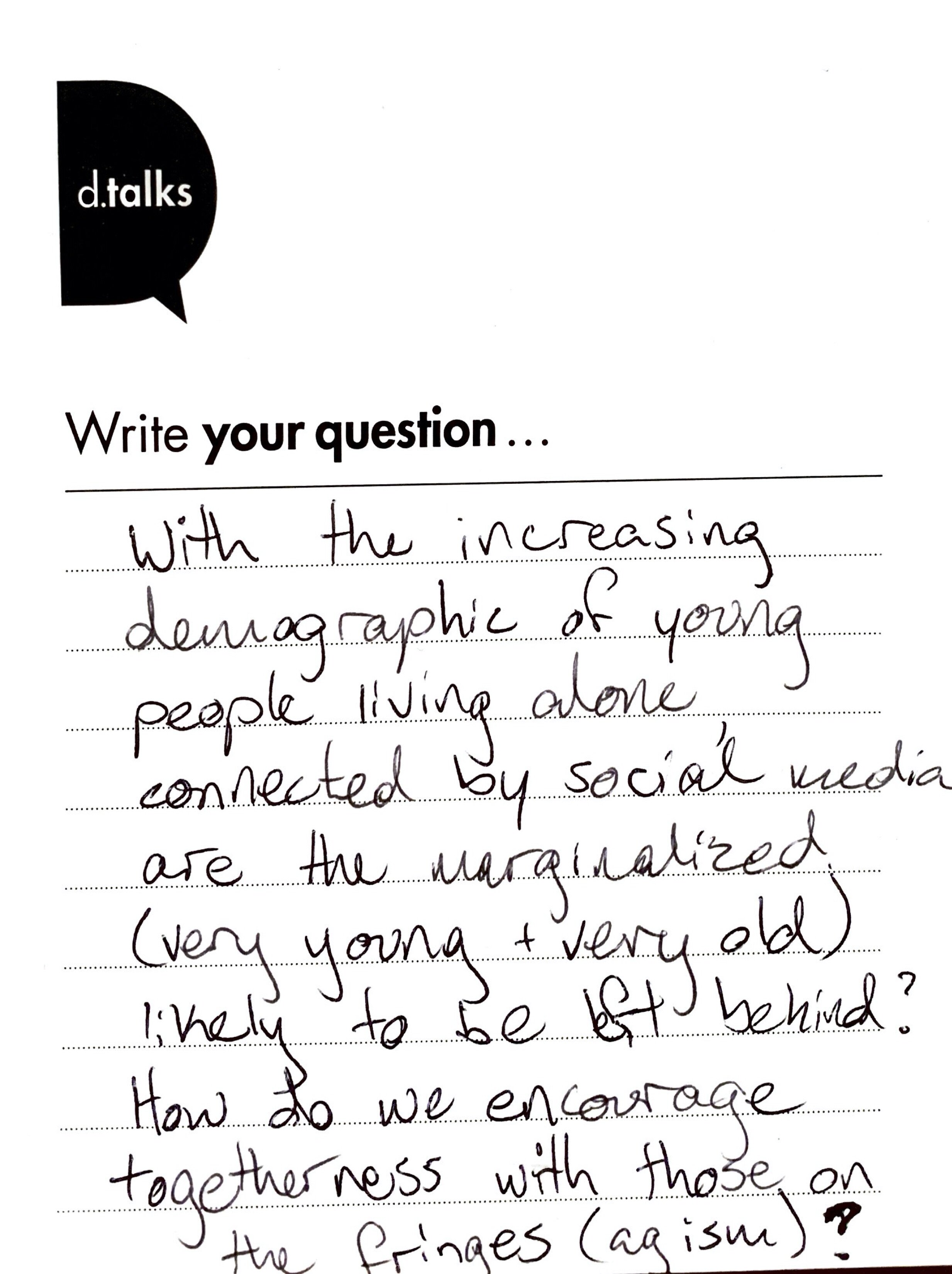

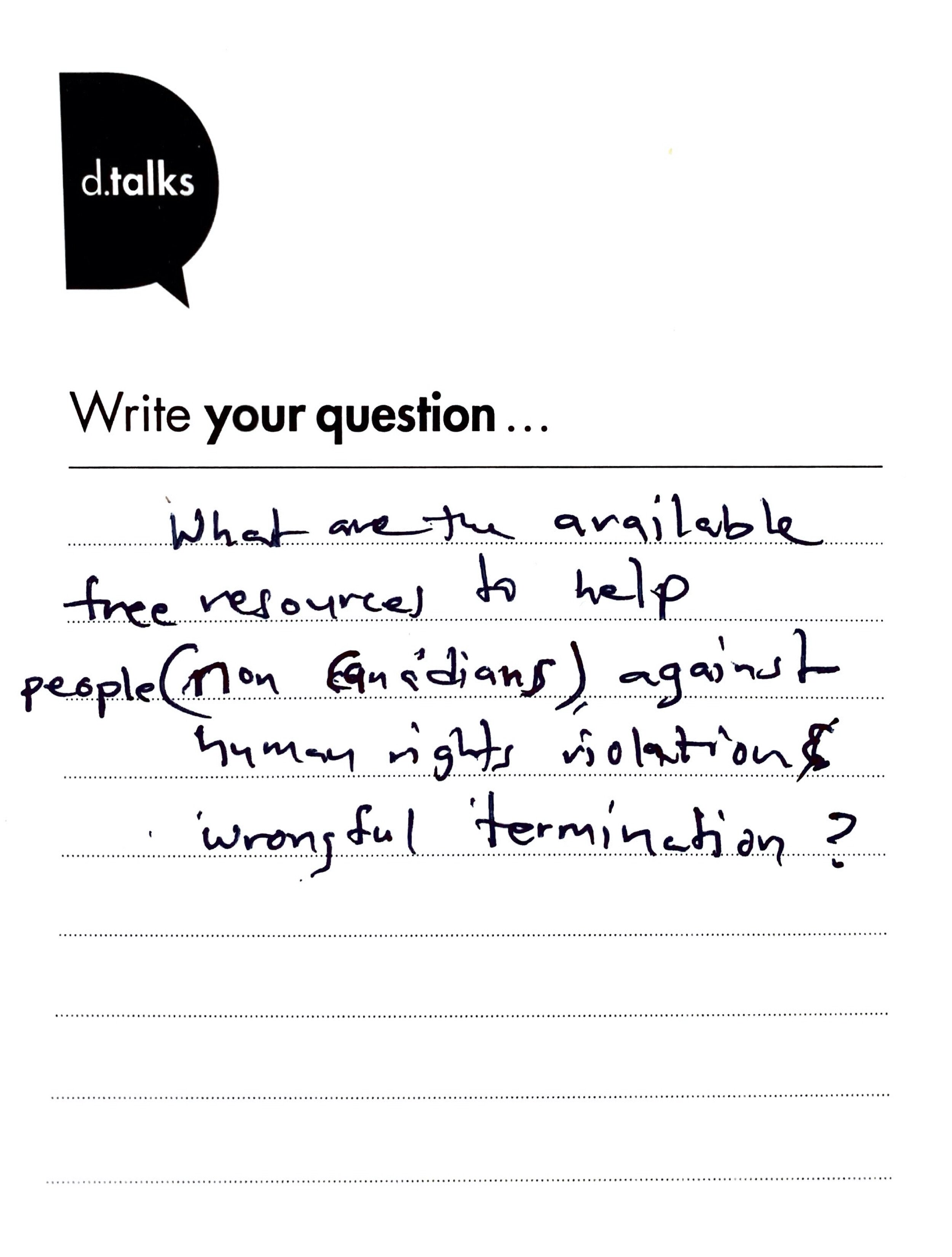

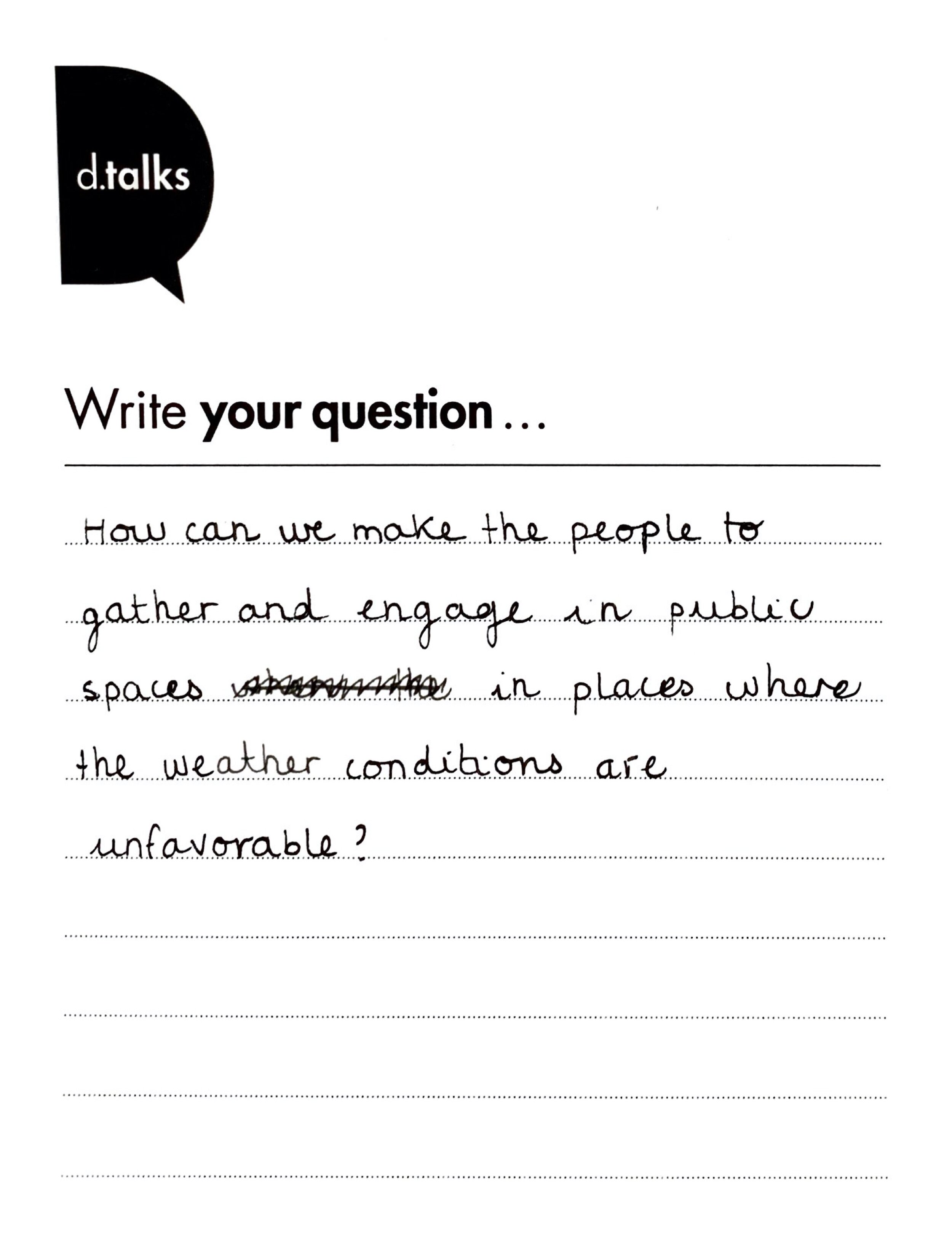

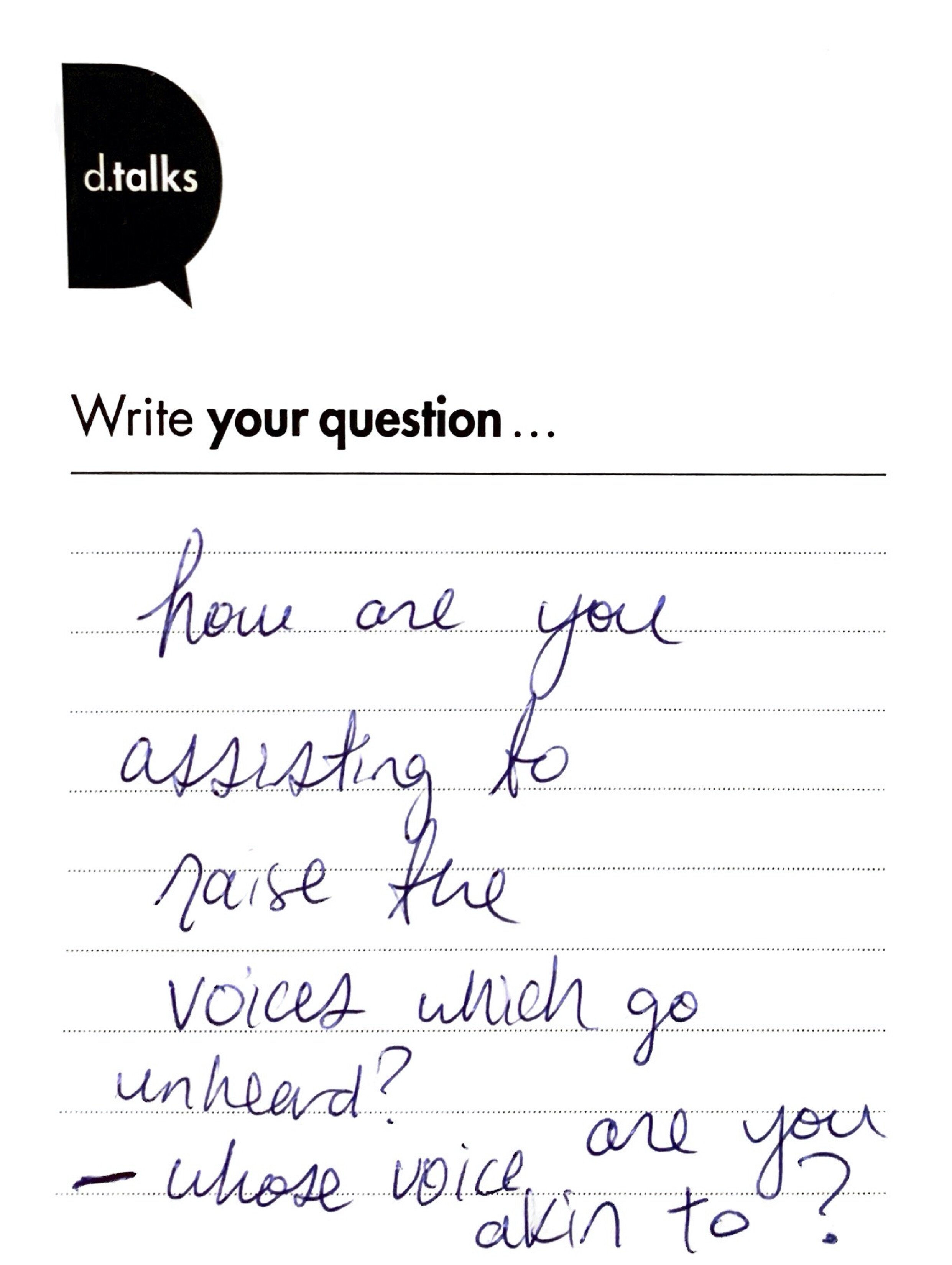

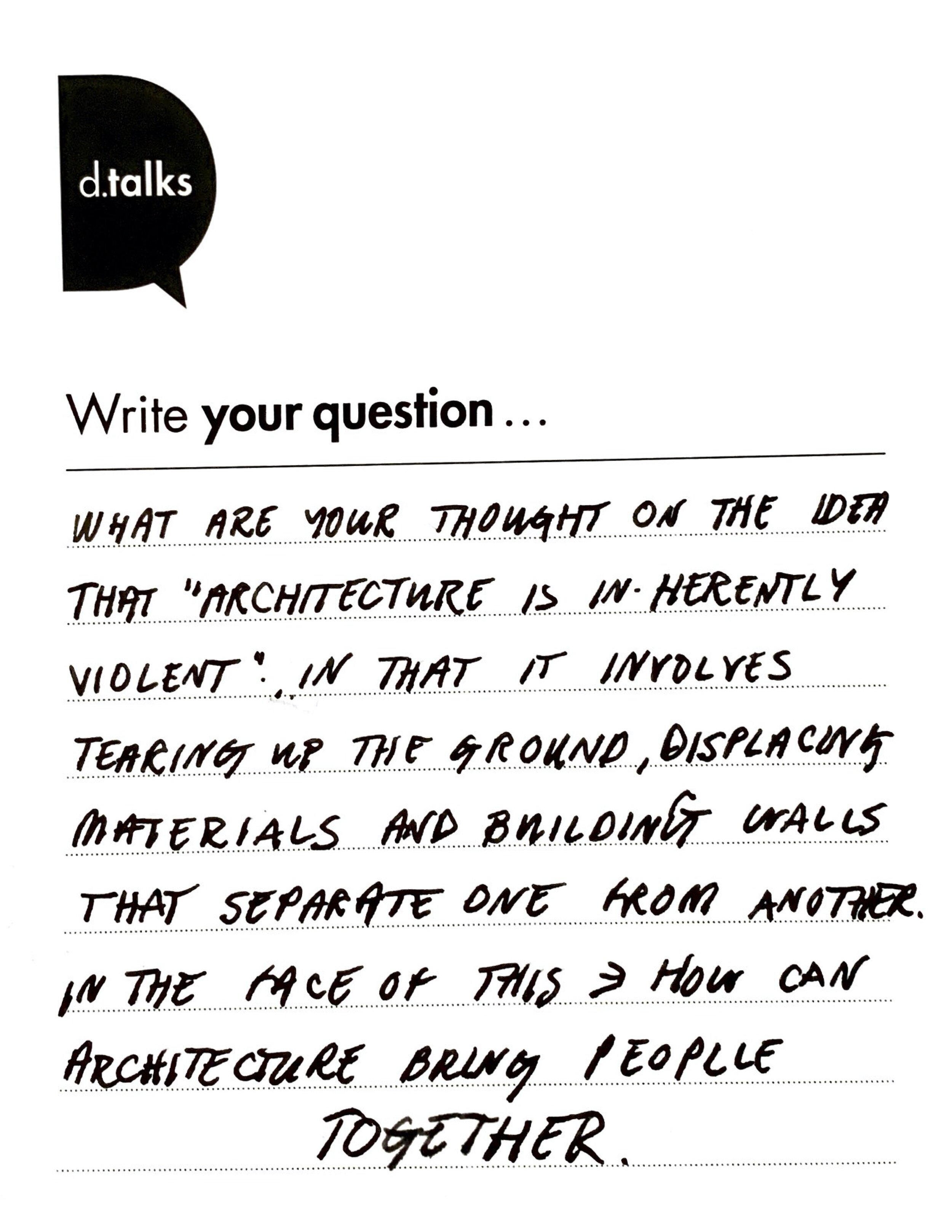

Photo by Allison Seto

Photo by Allison Seto

Photo by Allison Seto

Photo by Allison Seto

Photo by Allison Seto

Photo by Allison Seto

Photo by Allison Seto

Photo by Allison Seto

Photo by Allison Seto

Photo by Allison Seto

Photo by Allison Seto

Photo by Allison Seto

Photo by Allison Seto

Photo by Allison Seto

Photo by Allison Seto

Photo by Allison Seto

Photo by Allison Seto

Photo by Allison Seto

Photo by Allison Seto

Photo by Allison Seto

Photo by Allison Seto

Shannon Lanigan, Co-Founder and Managing Director of d.talks: photo by Allison Seto